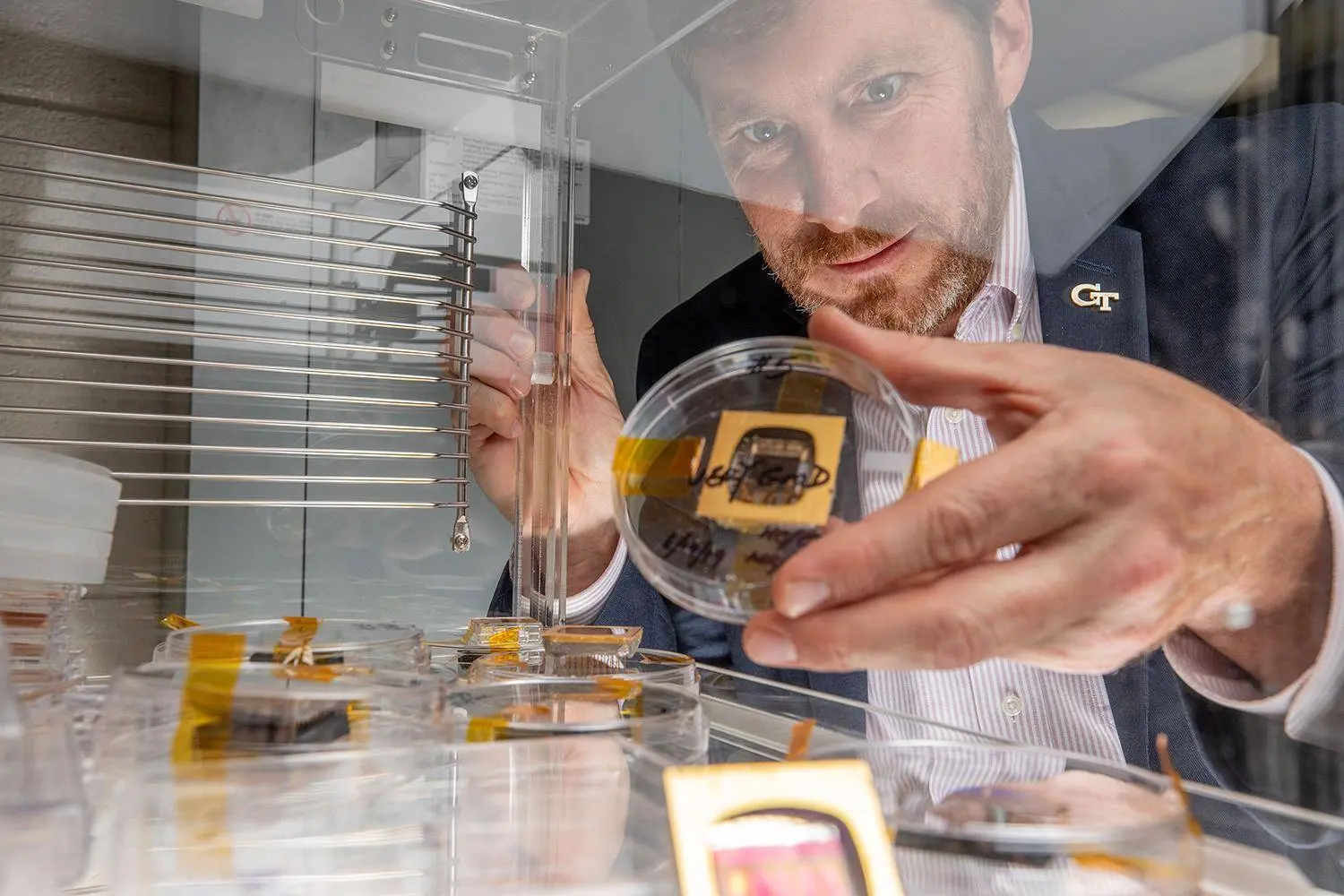

Space researcher. Materials scientist. Entrepreneur. And Yellow Jacket. The only thing missing on Jud Ready’s resume is “astronaut.” Not for lack of trying, though. Ready had hoped earning his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in materials science and engineering at Georgia Tech would lead him to a spot in NASA’s Astronaut Corps. Instead, it’s led him to the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), where his passion for space is alive and well.

1. What about space fascinates you?

It all goes back to my dad being interested in space. In first grade, we went to a how-to-use-the-library class, and I came across a book about the Mercury and Apollo astronauts. I checked it out and renewed it over and over again. I eventually finished it in second grade. So, I’ve had a lifelong commitment since then to space.

2. What drew you to engineering?

I grew up in Chapel Hill. In that same first grade class, we went to the University of North Carolina chemistry department. My mom is really into roses, and they froze a rose in liquid nitrogen then smashed it on the table. It broke into a million bits, and I was like, “What?!” The ability of science to solve the unknown grabbed me. And I had a series of very good science teachers — Mr. Parker in fifth grade, in particular. Then I took a soldering class in high school. We built a multimeter that I still have and still use, and various other things. And I suddenly discovered and started exploring engineering. Plus, I just like making things.

3. How did your career change from hoping to be an astronaut to being an accomplished materials engineer?

When I started looking at colleges, that was my primary interest: What school would help me become an astronaut the quickest. I applied to Georgia Tech as an aerospace engineer, but was admitted as an undecided engineering candidate instead. It was the best thing that could have happened. Later, I got hired as an undergrad by a professor who was doing space-grown gallium arsenide on the Space Shuttle. Ultimately, they offered me a graduate position. I accepted, because I knew you needed an advanced degree to be an astronaut — and for a civilian, a Ph.D. in a relevant career such as materials science.

I applied so many times to be an astronaut — every time they opened a call from 1999 until just a few years ago. Never got in. But I was successful at writing proposals and teaching. So I started doing space vicariously through my students, writing research proposals on energy capture, such as solar cells; energy storage, such as super capacitors; and energy delivery like electron emission. They’re all enabled by engineered materials.

For the full article, please visit Georgia Tech's College of Engineering Website.